Han Chinese | History, Population & Culture

As one of the world’s largest ethnic groups, the Han Chinese boast a civilization with a history of several millennia. Their culture, rooted in ancient traditions and continuous evolution, has significantly shaped East Asia and beyond. From the Yellow River Basin, the cradle of their civilization, the Han Chinese have spread across China and established communities in Southeast Asia and other regions. Throughout history, dynasties like the Han and Tang have left indelible marks on their cultural identity.

In this article, WuKong Education delve into the rich tapestry of Han Chinese history, population distribution, social practices, and cultural achievements, including their contributions to art, architecture, philosophy, and literature. We explore how the Han Chinese have maintained their cultural heritage while adapting to changing times, making them a vital part of both China’s past and its future.

Introduction to Han Chinese

The Han Chinese are the world’s largest ethnic group, with a rich and diverse history spanning over 4,000 years. As the dominant ethnic group in China, the Han Chinese have played a significant role in shaping the country’s culture, language, and civilization. With a population of over 1.4 billion, the Han Chinese account for approximately 92% of the Chinese population and 19% of the global population. The Han Chinese ethnic group is traditionally credited with the development of Chinese civilization, including the creation of the Chinese language, writing system, and cultural practices.

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!The origins of the Han Chinese trace back to the Yellow River Basin, where early agricultural tribes laid the foundations for what would become one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations. Over millennia, the Han Chinese have built a rich cultural heritage, marked by significant achievements in art, literature, philosophy, and science. Their influence extends beyond China’s borders, impacting neighboring regions and contributing to the global cultural mosaic.

Chinese History

The history of the Han Chinese is deeply intertwined with the broader Chinese history, tracing back thousands of years and encompassing numerous dynastic changes that have shaped the cultural and social fabric of East Asia. The Zhou dynasty, which followed the Shang dynasty, established a fully developed feudal system and introduced the Mandate of Heaven, significantly influencing Chinese civilization. The Han Chinese ethnic group represents the majority of China’s population and has played a pivotal role in the development of Chinese civilization. Throughout the annals of Chinese history, from the ancient Shang and Zhou dynasties to the more recent Qing dynasty, the Han Chinese have been at the forefront of cultural, political, and social evolution. Their history is marked by significant historical migrations, interactions with neighboring ethnic groups, and the establishment of powerful empires that have left an indelible mark on human history. The Han Chinese trace their origins to the Yellow River Basin, considered the cradle of Chinese civilization, where agricultural tribes began to flourish and develop the rich traditions that define Han culture today.

The Han Chinese civilization is regarded as one of the world’s oldest civilizations, with a continuous cultural heritage that has influenced not only China proper but also neighboring regions in East Asia. The Chinese language, closely associated with the Han ethnic group, has evolved over time and serves as a vital medium for preserving and transmitting Han Chinese culture. Throughout Chinese history, the Han Chinese have witnessed the rise and fall of dynasties such as the Qin, which established the first centralized empire, the Han dynasty that further consolidated power and cultural identity, and the Tang dynasty renowned for its cultural flourishing. Each dynasty contributed to the development of the Han Chinese civilization, leaving behind architectural marvels, literary works, and philosophical thoughts that continue to inspire and influence the world.

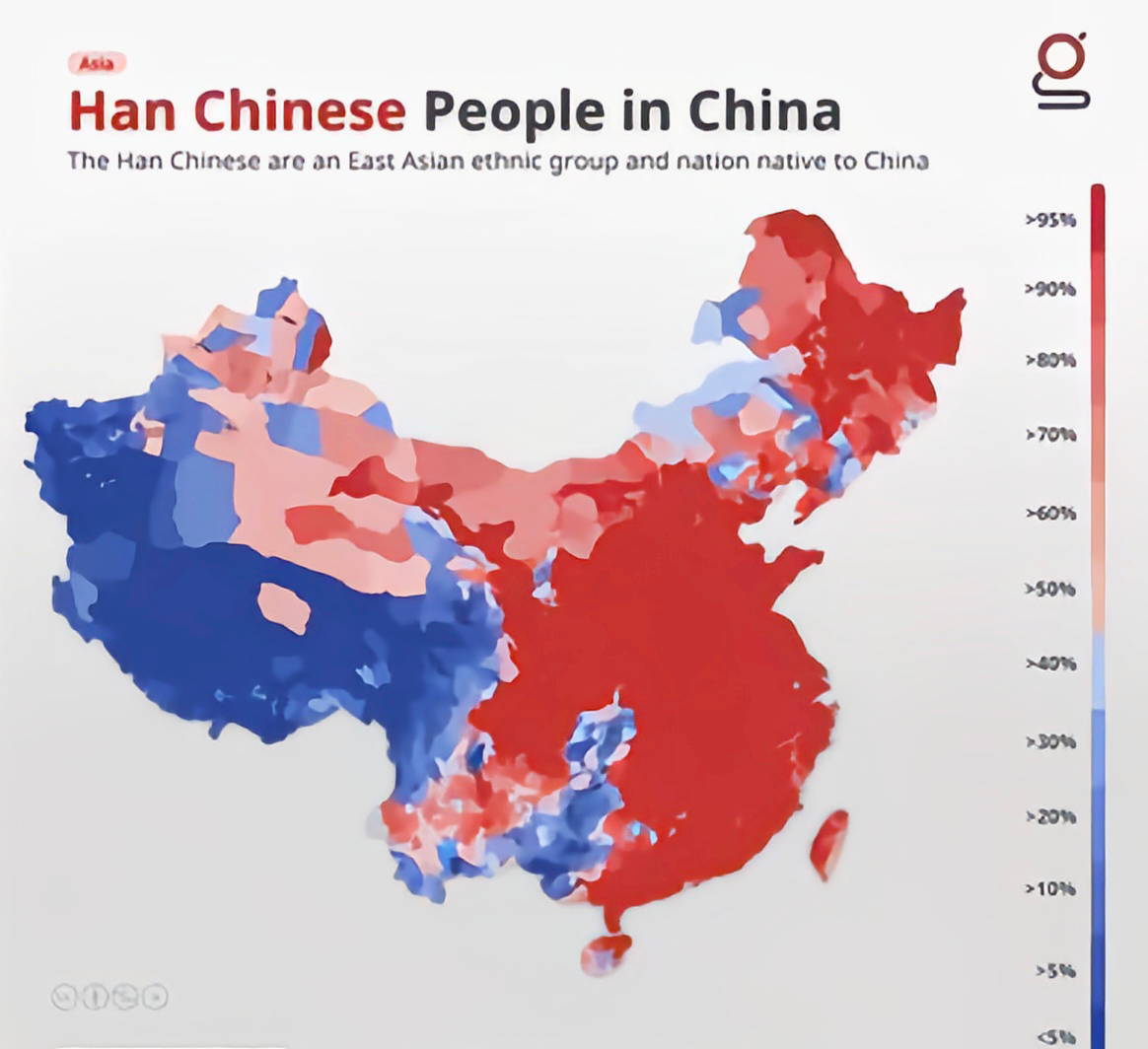

Han Chinese Population Distribution

The Han Chinese population is predominantly concentrated in China proper, which includes the central plains and the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River. However, significant populations of Han Chinese can also be found in other regions of China, such as northern China and areas that have experienced historical migrations. The cultural and historical interactions between the Han Chinese and Japan have also been significant, with Han Chinese culture influencing various aspects of Japanese civilization. Beyond China’s borders, the Han Chinese diaspora has established communities in various parts of Southeast Asia, including Singapore and Taiwan. In Singapore, the Han Chinese constitute a majority of the population and have made significant contributions to the country’s cultural and economic landscape. Similarly, in Taiwan, the Han Chinese have a rich cultural presence, with Mandarin serving as the primary language and various dialects such as Cantonese and Yue also spoken among different communities.

The total population of Han Chinese worldwide is vast, with the majority residing in mainland China. Their distribution across different regions has been influenced by factors such as economic opportunities, political circumstances, and cultural connections. In cities like Beijing and Shanghai, the Han Chinese form the backbone of urban society, contributing to the bustling cultural and economic life of these metropolitan centers. The population dynamics of the Han Chinese reflect their adaptability and resilience, as they have maintained their cultural identity while integrating into diverse environments across Asia and beyond.

Social and Cultural Practices

Han Chinese social and cultural practices are deeply rooted in traditions that emphasize family values, respect for ancestors, and social harmony. China’s historical experiences have influenced its preference for strong leadership to maintain order and prevent chaos, emphasizing the importance of achieving stability and social harmony within Han Chinese culture. Ancestor worship is a significant aspect of Han Chinese culture, where families honor their predecessors through rituals and offerings, believing in the continuity of family lineage and the guidance of ancestors in the lives of the living. This practice reinforces the importance of family and kinship ties within the Han Chinese community.

The concept of cultural identity is central to Han Chinese social practices, with traditions such as festivals, cuisine, and clothing serving as markers of their heritage. Chinese festivals like the Spring Festival and Mid-Autumn Festival are celebrated with great enthusiasm, involving family reunions, feasting, and various cultural activities that strengthen community bonds. Traditional Han Chinese clothing, such as the qipao and hanfu, reflects the aesthetic sensibilities and historical evolution of Han attire, often worn during special occasions to express cultural pride.

In terms of social structure, the Han Chinese have traditionally organized themselves into extended family units, with elders holding positions of respect and authority. The emphasis on filial piety, or respect for parents and elders, is a core value that influences intergenerational relationships and family dynamics. This value is not only evident in daily interactions but also in the way families care for their elderly members and pass down cultural knowledge and traditions.

Agriculture and Cultural Identity

Agriculture has been the foundation of Han Chinese society for millennia, shaping their cultural identity and way of life. The Han dynasty, following the Zhou and Qin dynasties, is seen as a golden age that solidified cultural identity, leading the Chinese people to identify themselves with the Han name and their written language termed as Han characters. The Yellow River Basin, with its fertile plains, provided the ideal conditions for the development of agricultural tribes that would eventually form the basis of the Han Chinese civilization. Traditional farming practices, including rice cultivation in the southern regions and wheat farming in the north, have not only sustained the population but also influenced cultural practices and dietary habits.

The Han Chinese agricultural calendar, which is closely tied to lunar cycles and seasonal changes, has guided farming activities and religious rituals. Festivals such as the Qingming Festival, which involves tomb sweeping and honoring ancestors, are directly related to agricultural cycles and the connection between the living and the deceased. The rich tradition of agricultural poetry and literature also reflects the deep bond between the Han Chinese and the land, with works often depicting the beauty of rural landscapes and the hardships and joys of farming life.

Agricultural surpluses enabled the development of trade and the growth of urban centers, which became hubs of cultural and artistic innovation. The exchange of goods and ideas between rural and urban areas contributed to the diversification of Han Chinese culture, while the stability provided by agriculture allowed for the flourishing of arts, crafts, and intellectual pursuits.

Family and Filial Piety

The family unit is of paramount importance in Han Chinese culture, serving as the fundamental building block of society. Filial piety, or xiao, is one of the core values that govern family relationships and is considered a cornerstone of Confucian ethics. It emphasizes the duties and responsibilities of children toward their parents, including obedience, respect, and care in old age. This value extends beyond the immediate family to include respect for elders within the extended family and the community.

Traditional Han Chinese family structures often involved multi-generational households, where grandparents, parents, and children lived together under one roof. The eldest male typically held authority within the family, making decisions on behalf of all members. Family celebrations, such as weddings and births, were marked by elaborate ceremonies that reinforced family bonds and cultural traditions. The concept of family honor was closely tied to individual behavior, with each member expected to uphold the family’s reputation through their actions.

In modern times, while family structures have become more diverse due to urbanization and changing social norms, the value of filial piety continues to influence intergenerational relationships. Many Han Chinese families still place a strong emphasis on caring for elderly parents and maintaining strong family connections, even as they adapt to contemporary lifestyles.

Religion

Religion in Han Chinese culture is a complex tapestry woven from various beliefs and practices, including ancestor worship, Buddhism, Taoism, and folk religions. Ancestor worship, as previously mentioned, is integral to family and community life, with shrines often found in homes and ancestral halls where offerings are made to honor forebears. This practice is believed to ensure the well-being of both the living and the deceased, maintaining a harmonious relationship between the two worlds.

Buddhism was introduced to China from India around the 1st century CE and has since become deeply embedded in Han Chinese religious life. Buddhist temples and monasteries dot the landscape, serving as centers for worship, meditation, and learning. Buddhist festivals, such as Vesak, which commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha, are widely observed and attract large numbers of devotees. The teachings of Buddhism, particularly those related to compassion, karma, and rebirth, have influenced Han Chinese philosophy and ethics.

Taoism, indigenous to China, also holds a significant place in Han Chinese religion. With its focus on the Tao, or the Way, Taoism emphasizes living in harmony with the natural order and the pursuit of immortality through various practices such as meditation and alchemy. Taoist priests perform rituals to balance the forces of nature and to seek blessings for the community. Taoist festivals, like the Chinese New Year, incorporate elements of Taoist mythology and rituals, blending seamlessly with other cultural celebrations.

Folk religions, characterized by the worship of local deities and nature spirits, vary by region but share common themes of seeking protection, fertility, and good fortune. Temples dedicated to deities such as Mazu, the goddess of the sea, are prevalent in coastal areas and serve as focal points for community gatherings and religious processions. These diverse religious practices coexist and interact, reflecting the pluralistic nature of Han Chinese spirituality.

Social Harmony

Social harmony is a fundamental ideal in Han Chinese society, deeply influenced by Confucian philosophy. Confucius emphasized the importance of maintaining order and harmony through the proper conduct of individuals within the family and society. The concept of “harmony without uniformity” encourages respect for diversity while striving for cohesion and stability. In traditional Han Chinese communities, social harmony was maintained through clear hierarchical relationships and mutual obligations between different members of society.

The Confucian emphasis on education as a means to cultivate virtuous individuals has contributed to the high value placed on learning and intellectual pursuits within Han Chinese culture. The imperial examination system, which selected officials based on their knowledge of Confucian classics, reinforced the connection between education and social mobility, promoting a meritocratic ideal. This system had a profound impact on Chinese society, shaping the bureaucratic structure and influencing the cultural emphasis on academic achievement.

In contemporary Han Chinese society, the pursuit of social harmony continues to manifest in various ways, such as community-building initiatives, cultural preservation efforts, and the promotion of ethical values. The government and various organizations often highlight the importance of social harmony as a foundation for national development and stability. However, like all societies, the Han Chinese community faces challenges in balancing traditional values with modern realities, requiring ongoing dialogue and adaptation to maintain social cohesion in an evolving world.

Han Chinese vs Other Chinese

When comparing the Han Chinese with other ethnic groups within China, it is important to recognize the rich diversity that exists within the Chinese nation. While the Han Chinese constitute the majority, there are 55 officially recognized minority ethnic groups in China, each with its own distinct culture, language, and traditions. These groups, such as the Zhuang, Hui, Manchu, and Uyghur, have made significant contributions to the tapestry of Chinese culture.

The Han Chinese culture has heavily influenced other ethnic groups through centuries of interaction, trade, and intermarriage. However, minority cultures have also impacted Han Chinese practices, creating a dynamic of mutual enrichment. For example, musical instruments, clothing styles, and culinary traditions from minority groups have been incorporated into broader Chinese culture. Despite these influences, minority ethnic groups have worked to preserve their unique identities, languages, and customs, often through cultural revitalization movements and official support for minority rights.

In regions with significant minority populations, such as Xinjiang and Tibet, cultural differences can be pronounced, reflecting distinct historical trajectories and geographical circumstances. The relationship between the Han Chinese and minority groups has at times been complex, shaped by policies aimed at promoting national unity and integration. Efforts to protect and celebrate China’s diverse cultural heritage continue to evolve, reflecting a commitment to honoring both the commonalities and differences that make up the Chinese nation.

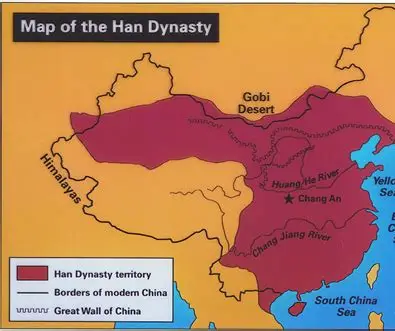

Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) stands as a golden age in Chinese history, leaving an indelible legacy on the Han Chinese ethnic group and their civilization. The Han Chinese are the world’s largest ethnic group, and their influence during the Han dynasty extended beyond China’s borders, contributing to the global cultural mosaic. The dynasty’s political and administrative innovations established a model for subsequent Chinese governments, with a centralized bureaucracy staffed by scholar-officials trained in Confucian principles. This system emphasized merit and learning, setting a precedent for the importance of education and ethical conduct in public service.

Economically, the Han dynasty prospered through agricultural advancements, the development of trade networks such as the Silk Road, and the growth of industries like textiles and metallurgy. Cultural achievements during this period were equally remarkable, with significant developments in literature, art, and technology. The Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, compiled during the Han era, remains a vital historical text that provides invaluable insights into early Chinese history and the Han Chinese worldview.

The Han dynasty’s influence extended beyond its borders, as it engaged in diplomatic relations and cultural exchanges with neighboring regions. The expansion of Han territory and the spread of Han culture laid the groundwork for the Sinicization of neighboring peoples, contributing to the formation of the Han Chinese as the dominant ethnic group in the region. Even after the dynasty’s fall, the cultural and political traditions established during the Han period continued to shape Chinese society, with later dynasties often seeking to emulate or reform Han institutions.

Chinese Painting

Chinese painting, an integral part of Han Chinese culture, reflects the deep connection between art and nature that is characteristic of Chinese aesthetics. Traditional Chinese painting, or guohua, employs ink and brush on paper or silk, emphasizing the expressive quality of brushstrokes and the harmony between elements. The art form is categorized into various styles, including figure painting, landscape painting (shanshui), and flower-and-bird painting, each with its own techniques and symbolic meanings.

Landscape painting, in particular, holds a special place in Han Chinese artistic tradition, often depicting vast, majestic scenes that convey a sense of the sublime and the transient nature of human existence within the natural world. The use of ink wash techniques allows artists to create variations in tone and texture, suggesting mist, distance, and the play of light and shadow. Many famous landscape painters, such as Guo Xi and Ni Zan, have left behind masterpieces that are studied and revered for their technical skill and spiritual depth.

Throughout history, Chinese painting has been influenced by philosophical ideas, especially those of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Confucian themes of social order and moral virtue sometimes appear in figure paintings, while Buddhist motifs and Taoist concepts of natural spontaneity inform other works. The evolution of Chinese painting styles over dynastic periods reflects changes in cultural values, technological advancements, and the exchange of ideas with other cultures.

In modern times, Chinese painting continues to thrive, with contemporary artists both preserving traditional methods and innovating by incorporating new materials and concepts. The art form serves as a bridge between the past and present, allowing viewers to connect with the rich heritage of Han Chinese culture while exploring new artistic expressions.

Chinese Architecture

Chinese architecture represents another magnificent aspect of Han Chinese cultural achievement, distinguished by its unique structural principles, aesthetic values, and symbolic meanings. Traditional Chinese buildings are characterized by their use of timber framing, upward-sweeping roofs with decorative eaves, and symmetrical layouts that reflect Confucian ideals of order and harmony. The concept of feng shui, which seeks to align buildings with natural and cosmic forces for optimal balance, has also significantly influenced architectural design.

The Forbidden City in Beijing stands as the quintessential example of Chinese imperial architecture, showcasing the grandeur and sophistication of Ming and Qing dynasty construction. Its intricate layout, with numerous halls and courtyards arranged along a central axis, symbolizes the hierarchical order of the imperial court and the universe. Similarly, the Great Wall of China, a testament to ancient engineering prowess, winds its way across northern China, serving as a defensive structure and a powerful symbol of Chinese resilience and unity.

Beyond imperial structures, traditional Han Chinese residential architecture varies by region but often features enclosed courtyards, screen walls, and decorative elements such as carved windows and painted beams. The design of these homes aimed to provide comfort, privacy, and a connection to nature, with gardens and water features integrated into the living spaces. Religious architecture, including Buddhist temples and Taoist monasteries, incorporates elements that facilitate spiritual practices and reflect doctrinal principles, such as the orientation of temple axes and the arrangement of sacred spaces.

In urban planning, ancient Chinese cities were designed with careful attention to defense, trade, and ceremonial functions. The use of grid patterns, city walls, and central marketplaces created organized and efficient urban environments. The integration of architectural elements with surrounding landscapes, whether in the form of palace complexes or rural villages, underscores the Han Chinese philosophy of living in harmony with nature.

Chinese Pottery

Chinese pottery and ceramics have a history spanning thousands of years and represent a significant contribution of the Han Chinese to the world of art and craftsmanship. From the early Neolithic pottery of the Yangshao and Longshan cultures to the sophisticated porcelain of the Song and Ming dynasties, Chinese ceramics have evolved in technique, style, and function. The discovery of pottery shards with inscriptions in the Shang dynasty indicates the early use of ceramics for both utilitarian and ritual purposes.

One of the most renowned types of Chinese ceramics is blue-and-white porcelain, which gained prominence during the Yuan dynasty and reached its peak in the Ming dynasty. Characterized by cobalt blue designs on a white background, these pieces were highly valued for their beauty and technical excellence. Exports of blue-and-white porcelain along the Silk Road and maritime trade routes introduced Chinese ceramic art to the world, influencing pottery traditions in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

The production of Chinese ceramics involved specialized techniques such as high-temperature firing, glazing methods, and precise brushwork. Different regions became known for specific ceramic styles; for example, Ding ware from Hebei was famous for its delicate white glaze, while Ru ware from Henan was celebrated for its subtle crackle glaze and elegant forms. The art of ceramics was not only a commercial activity but also a vehicle for expressing cultural themes, with motifs ranging from floral patterns and calligraphy to mythological scenes and symbols of good fortune.

In addition to porcelain, Chinese pottery includes a wide variety of earthenware, stoneware, and glazed ceramics used in daily life, religious ceremonies, and burial practices. The terra-cotta warriors of the Qin dynasty, discovered in the emperor’s mausoleum, are a spectacular example of pottery used for funerary purposes, showcasing the technical and artistic capabilities of ancient Chinese craftsmen.

Chinese Music

Chinese music, with its ancient traditions and diverse forms, is an essential component of Han Chinese cultural expression. The history of Chinese music can be traced back to the earliest dynasties, with instruments such as the guqin (seven-stringed zither) and sheng (mouth organ) appearing in archaeological records and classical texts. Music in Han Chinese culture has served multiple functions, including ritual, court entertainment, scholarly cultivation, and folk celebration.

Confucian philosophy emphasized the role of music in moral education and social harmony, believing that proper music could cultivate virtues and maintain order. As a result, ritual music, known as yanyue, developed as a codified system used in court and ancestor worship ceremonies. The music followed strict guidelines regarding pitch, rhythm, and instrumentation, symbolizing the hierarchical and orderly nature of society.

Traditional Chinese music is based on a pentatonic scale and employs a variety of instruments categorized into eight classes according to the materials they are made from: metal, stone, silk, bamboo, gourd, clay, leather, and wood. Each instrument has its distinct sound and cultural significance. For example, the guzheng, a plucked string instrument, is often associated with elegance and grace, while the suona, a loud double-reed instrument, is commonly used in folk celebrations and processions.

Folk music traditions vary across Han Chinese regions, reflecting local customs and lifestyles. Folk songs, dances, and operas convey stories of love, labor, historical events, and regional pride. The Chinese opera, with its stylized performances combining singing, dialogue, acting, and acrobatics, is a comprehensive art form that has produced regional variants such as Peking opera, Kunqu, and Yue opera. These operas are celebrated for their elaborate costumes, distinctive vocal techniques, and dramatic storytelling, serving as a vital medium for preserving and transmitting Han Chinese cultural heritage.

In the modern era, Chinese music has undergone transformations through the incorporation of Western musical elements and the development of new genres. However, traditional music continues to thrive in cultural events, television programs, and international performances, attracting new audiences and ensuring the continuity of this ancient art form.

FAQ About Han Chinese

What is Han Chinese?

The Han Chinese are the largest ethnic group in China, accounting for over 90% of the country’s population. They have a history dating back thousands of years and have made significant contributions to Chinese civilization, culture, and society.

What do Han Chinese Look Like?

The physical appearance of Han Chinese people is typically characterized by features common to East Asians, such as black hair, dark eyes, and yellowish skin. However, there is a wide range of individual variation in terms of facial features, body types, and other physical characteristics.

During Which Chinese Dynasty was Confucius Born? Zhou, Shang, Han, Qin.

Confucius was born during the Zhou Dynasty. The Zhou Dynasty was a period of great philosophical and cultural development in Chinese history, and Confucius’s teachings had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese society and culture.

Conclusion

The Han Chinese represent a vibrant and enduring civilization with a profound impact on global history and culture. Through their rich traditions, social practices, artistic achievements, and philosophical thought, the Han Chinese have contributed immensely to the development of human society.

As they continue to navigate the complexities of the modern world, the Han Chinese maintain a strong connection to their heritage while embracing innovation and change. Their cultural legacy serves as a source of inspiration and a foundation for future generations to build upon, ensuring that the story of the Han Chinese remains a vital and evolving chapter in the annals of world civilization. If you want to learn more about Chinese culture, please follow Wukong Chinese.

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!

Bella holds a Master’s degree from Yangzhou University and brings 10 years of extensive experience in K-12 Chinese language teaching and research. A published scholar, she has contributed over 10 papers to the field of language and literature. Currently, Bella leads the research and development of WuKong Chinese core courses, where she prioritizes academic rigor alongside student engagement and cognitive development. She is dedicated to building a robust foundation for young learners covering phonetics (Pinyin), characters, idioms, and classical culture while ensuring that advanced courses empower students with comprehensive linguistic mastery and cultural insight.

![Year of Monkey Chinese Zodiac [2026 Full Guide] Year of Monkey Chinese Zodiac [2026 Full Guide]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/询问中文早上好的说法-22-520x293.png)

![Spring Festival Couplets: A Timeless Chinese New Year Tradition [2026 Horse Year Updated] Spring Festival Couplets: A Timeless Chinese New Year Tradition [2026 Horse Year Updated]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/jimeng-2026-02-11-6820-中国传统红色剪纸艺术,一匹造型优美的马,线条流畅,周围环绕着祥云、梅花和福字-520x293.webp)

Comments0

Comments